Path of the Rapier

“The reason as I take it, is because that amongst Knights, Captains, and valiant Soldiers, the Rapier is it which sheweth who are men of armes and of honor, and which obtaineth right for those which are wronged: and for this reason it is made with two edges and one point, and being the weapon which ordinarily Noble men, Knights, Gentlemen and Soldiers wear by their side, as being more proper and fit to be worn then other weapons: therefore this is it which must first be learned, especially being so usual to be worn and taught.”

VINCENTIO SAVIOLO, 16TH CENTURY ITALIAN FENCING MASTER AND AUTHOR OF HIS PRACTISE, IN TWO BOOKES.

The Path of the Rapier section of our website has lists of historical treatises and manuscripts that teach how to learn rapier sword fighting techniques. These are all resources studied within the HEMA (historical European martial arts) community of historical sport rapier fencers, instructing in different rapier fighting styles. They are also studied for the SCA rapier event fighting, too, in the Society for Creative Anachronism.

Originally called the espada ropera and evolving from the spada da lato or side-sword, the rapier sword was the preeminent dueling weapon during the 16th to 17th centuries. It developed in a time where significant class change was occurring in Europe and the wearing of a sword became both for self-defense and for fashion by nobles and civilians alike. Rapier fighting styles became very popular, surpassing the study of other types of swords during this period of time and eventually leading to the abandonment of other kinds of swords such as the two handed long sword.

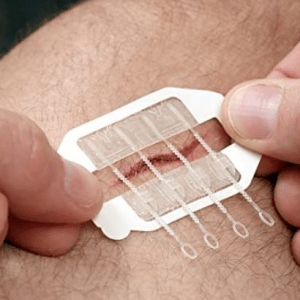

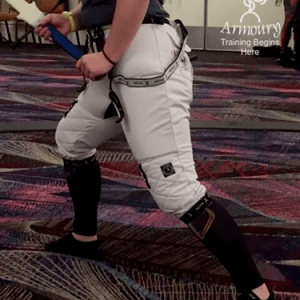

In contrast to its depiction in popular media the rapier sword is not a ‘light weapon’, and due to the manner in which combat is performed to fence with one can be a grueling workout. The rapier sword is held with one hand and the arm extended, so although the entire weight of the weapon may only be two to four pounds, the amount of force actually applied to your wrist is many times over that. Holding a rapier in any of the guards for an extended period will quickly tire your arm out while performing rapier sword fighting techniques, so building up stamina in your arms with constant practice is necessary to fully perform rapier fighting styles.

Additionally, the utilization of difficult to maintain torso and leg positions in its guards coupled with the usage of quick lunges and recoveries to strike, makes handling a rapier sword a more physically challenging activity than long sword fencing is given the same amount of time spent practicing. This is because the long sword is generally held with two hands and uses more natural body postures that are easiest to hold and switch between. While the rapier is a weapon that is focused on dexterity the amount of physical stamina and strength required to properly engage in rapier fencing often surprises beginners. Performing rapier sword fighting techniques daily in a school is an amazing workout for this reason.

For more detailed information about the characteristics of rapiers please read our article, ‘What exactly is a rapier? Clearing up common misunderstandings‘.

Something to note is that there are many rapier treatises that exist describing different rapier fighting styles. Not every manuscript that has ever been written about rapier sword fencing will be mentioned on this page. This is just a short overview of the different traditions to assist a beginner in identifying and locating source material that is commonly studied by the HEMA community, and provide some general knowledge on the subject.

Italian Rapier Fighting Styles

The most popularly studied historical rapier style is the Italian tradition. While there are many masters within this rapier fighting style who influenced it here I will talk briefly about the most important ones studied today by HEMA practitioners, so the most common rapier sword fighting techniques are from these masters.

Until the advent of the smallsword and the French schools, the Italians and to a lesser degree the Spanish, enjoyed the role of the most sought after teachers of rapier fencing. Among the Italian the Swept-hilted rapier was the most popular style of hilt guard.

SWEPT HILT RAPIERS FROM HERMITAGE MUSEUM, SAINT PETERSBURG, RUSSIA. The rapier sword has its roots in the usage of the side-sword (spada da lato), specifically the type used by Bolognese (Dardi) tradition fencing master Achille Marozzo and described in his treatise Opera Nova dell’Arte delle Armi (The New Text on the Art of Arms”) which he published in 1536 in the Italian city of Modena.

In response to Marozzo’s work in 1553 Camillo Agrippa published and printed Trattato di Scientia d’Arme, con vn Dialogo di Filosofia (“Treatise on the Science of Arms, with a Philosophical Dialogue”). This original work presented a unique new system of swordsmanship based on his knowledge of geometry and mechanics, and championed the idea that the weapon should be held in a frontal position before the body to protect it, and never held in a rear position as Marozzo described. Agrippa’s work would heavily influence the development of Italian rapier fencing through the rest of Europe. The unique aspects of rapier sword fighting techniques can be traced back to Aggrippa.

- Fencing: A Renaissance Treatise (Agrippa)

In 1570 Giacomo di Grassi published the fencing treatise Ragione di adoprar sicuramente l’Arme (“Discourse on Wielding Arms with Safety”). In 1594 the work was translated into English under the title of His True Arte of Defence and became one of the most influential rapier texts in Elizabethan era England and would later influence smallsword fencing, too.

Giovanni Antonio Lovino produced Modo di cacciare mano all spada (“Method of Putting Hand to the Sword”, MS Italien 959) in 1580, created for French king Henry III. This manuscript is located at the The Bibliothèque nationale de France and copies of it can be difficult to locate so I am including a direct link to the plates at the Gallica. The manuscript covers a variety of weapons, including early rapier sword fighting techniques.

Regole di moltio cavagliereschi essercitii (“Rules of Many Knightly Exercises”) is a manual created by Federico Ghisliero in 1587. It primarily discusses rapier sword fencing but also includes pages devoted to mounted combat with the lance, as well as defense against a mounted opponent using a rapier.

In 1595 the book His Practise, in Two Bookes was published in English by Italian fencing master Vincentio Saviolo, who had taken up residence in London in 1590 to teach the rapier fighting style described in his manual.

Salvator Fabris was a 16th century knight, a member of the Order of Seven Hearts. In 1601 he produced a three volume manuscript titled Scientia e Prattica dell’Arme (“The Science and Practice of Arms”, GI kongelig Samling 1868 4040) and in 1606 his manual Lo Schermo, overo Scienza d’Arme (“On Defense, or the Science of Arms”) was published. His work was highly influential on later fencing masters and frequently republished for over a hundred years, becoming an important rapier fighting style.

Nicoletto Giganti published known two books rapier fencing during his lifetime; the first is Scola, overo teatro (“School, or Fencing Hall”) published in 1606, and the second is Libro secondo di Niccoletto Giganti (“Second Book of Niccoletto Giganti”) in 1608. The latter was considered to be a lost book until recently having been rediscovered and translated into modern English. The former was seemingly popular for its time, enjoying numerous reprints and influencing the development of further rapier sword fighting techniques.

- Venetian Rapier: Nicoletto Giganti’s 1606 Rapier Fencing Curriculum

- Nicoletto Giganti’s The School of the Sword: A New Translation by Aaron Taylor Miedema

Ridolfo Capoferro wrote and published his own book of fencing titled Gran Simulacro dell’Arte e dell’Uso della Scherma (“Great Representation of the Art and Use of Fencing”) in 1610. It is worth mentioning for many years during the early revival of Historical European fencing Capoferro was the most studied of historical masters as his work is commonly cited by historians of fencing, and is still popular among rapier fighting styles today.

- Ridolfo Capoferro’s the Art and Practice of Fencing: A Practical Translation for the Modern Swordsman

Francesco Alfieri published a number of different treatises during his lifetime but as pertains to the rapier, he published La Scherma (“On Fencing”) in 1640, followed by a new edition in 1653 titled L’arte di ben maneggiare la spada (“The Art of Handling the Sword Well”) which included a new section on the use of the spadone.

Pallavicini 1670 and 1671 (might not be Destreza) which criticized the Neapolitan style developed by Giovan Battista Marcelli.

Giovan Battista Marcelli died in 1685 and his treatise was published in 1686 by his son. He is considered the origin of the Neapolitan school of Italian fencing.

1675 Miguel Pérez de Mendoza y Quijada published Resumen de la verdadera destreza de las armas, en treinta y ocho asserciones.

More biographical information about these masters can be read at their respective Wiktenauer pages.

Learning Italian Rapier

There are a number of excellent books written to help people understand how to do Italian based rapier fencing and rapier sword fighting techniques. Here is a short list of a few of them.

- Fundamentals of Italian Rapier

- The Duellist’s Companion

- The Art of the Rapier: A Manual for Today’s Fencers

- Introduction to the Italian Rapier: A Complete Curriculum for Training and Fencing with the Italian Rapier

Spanish Rapier

Also referred to as the ‘Destreza’ tradition. The word destreza literally translates to “dexterity” or “skill, ability”, and thus la verdadera destreza means “the true skill” or “the true art”. This is a decidedly different tradition of Spanish sword fighting than Esgrima (“fencing”), which was the kind of common fencing that was popularly used prior to the creation of Destreza. Among the Spaniards in the 1600s the Cup-hilted rapier was the most popular, possibly as a result of the defensive-oriented nature of Destreza, with a philosophy that ‘true art’ in fencing comes from a style that provides total protection to the fencer.

In 1569 Don Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza published De la Filosofia de las Armas y de su Destreza y la Aggression y Defensa Cristiana (“On the Philosophy of Arms and its Skill, and Christian Offense and Defense”). Carranza’s treatise presented a new system of rapier fencing based on early Renaissance geometry, Christian philosophy and Aristotelian physics which he called la Verdadera Destreza (“The True Skill”) and this is considered the establishment of the Destreza tradition. It had heavy influence from the work of Italian fencing theorist Camillo Agrippa.

A student of Carranza by the name of Don Luis Pacheco de Narváez published Libro de las Grandezas de la Espada (“A Book on the Greatness of the Sword”) in 1600. He would later write Nueva ciencia, y filosofía de la destreza de las armas (“The New Science and Philosophy of Skill at Arms”) in 1632 but doesn’t seem to have been published until forty years later, well after his death. Pacheco’s work focused on correcting perceived flaws he saw in Carranza’s work and these efforts ultimately separated the Destreza tradition into two competing camps, called Carrancistas and Pachequistas.

In 1628 Dom Diogo Gomes de Figueyredo produced a book of rapier fencing titled Oplosophia e Verdadeira Destreza das Armas (“Hoplosophy and the True Skill of Arms”, MS Vermelho.nº.91).

Gérard Thibault d’Anvers studied the Destreza tradition and is the author of the 1628 manual Academie de l’Espée (“Academy of the Sword”). Dutch in origin d’Anvers studied rapier fencing in Spain and then returned to the Netherlands where he became a well known figure for his fencing skill. His book is considered one of the most elaborately decorated and detailed of fencing instructional books.

- The Academy of the Sword

In 1640 Luis Méndez de Carmona Tamariz would produce Libro de la destreza berdadera de las armas ( Book of the True Skill of Arms).

The Destreza tradition would eventually as, with the French rapier tradition, gradually transform into usage of the smallsword.

You can read more information about some these masters on their biographical pages at Wiktenauer

- Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza

- Luis Pacheco de Narváez

- Dom Diogo Gomes de Figueyredo

- Gérard Thibault d’Anvers

German Rapier

The rapier sword had some popularity among the Germans as well. One of the most popular hilt designs for the rapier today is the Pappenheim-hilt rapier, or Pappenheimer, which is named for Count Gottfried Heinrich Graf zu Pappenheim, a famous field marshal of the Holy Roman Empire who served during the Thirty Years War. This style of hilt became popular throughout Europe due to its two shell guards which provide great protection to the hands.

Joachim Meyer is primarily studied in the HEMA community for his long sword plays but he also described plays for the rapier, too. Meyer produced three treatises during his lifetime; the Joachim Meyers Fäktbok (MS A.4º.2) sometime in the 1560s; the Fechtbuch zu Ross und zu Fuss (“Manual on Fencing, on Horse and on Foot”; MS Varia 82) and the Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (“A Thorough Description of the Art of Fencing”). The third treatise was published and printed using woodblocks in 1570 and unlike the previous two manuscripts is a comprehensive treatise where he claimed to teach the entire art of fencing using several weapons, including the rapier which Meyer noted was becoming popular among the Germans. Meyer’s system integrated the core philosophies of the Liechtenauer tradition with material that seems derived from the treatise of Achille Marozzo.

In 1611 Michael Hundt published a treatise of rapier fencing titled Ein new Kůnstliches Fechtbuch im Rappier (“A New Art-Filled Fencing Manual on Rapier”).

The very next year in 1612 Jakob Sutor von Baden published Neu Künstliches Fechtbuch which included instruction on the rapier with material seemingly derived from both Hundt and Meyer’s previous works.

In 1664 Jean Daniel L’Ange produced a short treatise titled Deutliche und grůndliche Erklårung der Adelichen und Ritterlichen freyen Fecht-Kunst (“A Clear and Thorough Explanation of the Noble, Chivalric, and Free Art of Fencing”) that described the usage of the rapier. The work was republished in 1708. Notable in this manual is a statement that L’Ange makes pertaining to why the rapier was superior to a long sword.

“A big sword is very dangerous in our times because it is more difficult to [carry] around with clothing than a smaller thrusting sword, which can easily be worn.” He also writes that “it is possible to kill a man who is armed with a gun in a short range, when he stands close to you[,] with the help of the rapier, because of the highly effective thrusting techniques [that] will save your life, rather than with the slower cutting of a bigger sword or a sabre. You may even be able to kill him, before he can take his gun out of its halter, before he can make the first shot”.

JEAN DANIEL L’ANGE, DEUTLICHE UND GRŮNDLICHE ERKLÅRUNG DER ADELICHEN UND RITTERLICHEN FREYEN FECHT-KUNST

Theodori Verolini would produce Deutliche und grůndliche Erklårung der Adelichen und Ritterlichen freyen Fecht-Kunst (“A Clear and Thorough Explanation of the Noble, Chivalric, and Free Art of Fencing”) in 1664, which seems largely based on Meyer’s work.

In 1671 Johannes Georges Bruchius published an extensive fencing manual entitled Grondige Beschryvinge van de Edele ende Ridderlijcke Scherm- ofte Wapen-Konste (“Thorough Description of the Noble and Knightly Fencing- or Weapon-Art”). It was published in Leiden by Abraham Verhoef, and treated the use of the single rapier in Meyer’s manner, which was itself heavily influenced by the rapier sword fighting techniques and teachings of the Italian master Salvator Fabris.

You can read more biographical information about these German rapier masters at their Wiktenauer pages

French Rapier

Interestingly enough, the historical methods of French rapier fencing is not an area studied as commonly within the modern HEMA community. This is despite the fact that the French rapier fencing tradition has had the most influence on the modern sport of fencing, and it eventually replaced both Spanish and Italian styles in the 16th century as the rapier developed into the smallsword. In fact, the foil was developed within the French fencing tradition as a safer training tool than just putting balls or buttons on the tips of rapiers, which was a common method in rapier training. This would eventually lead to the creation of modern sport fencing. I will briefly summarize in this section how that transformation occurred.

The foundation of Spanish rapier fencing is rooted upon the formation of the Académie des Maistres en faits d’armes de l’Académie du Roy by Charles IX of France on December 15th 1567.

Henry de Sainct Didier, a fencing master produced by this school, authored a 1573 treatise titled Traicté contenant les secrets du premier livre (Treatise containing the secrets of the first book on the single sword).

In 1610 fencing master François Dancie would publish his Discours des armes et methode pour bien tirer de l’espée et poignard (Discourse Of Arms And Method To Properly Fence With The Sword And Dagger) and another manual, L’espée de combat (The Sword of Combat) in 1623 which described a system of rapier fencing.

André Desbordes would also publish in 1610 a treatise named Discours de la théorie et de la pratique de l’excellence des armes (“Discourse on Theory, Practice, and Excellence at Arms”).

In 1653 Charles Besnard would produce a fencing treatise, Le Maistre d’Armes, whose material foreshadowed the development of the smallsword. In his treatise he writes, “Why does a man with little skill, courageous but lacking in judgment, often win with sword in hand over someone who would beat a hundred like him with the foil [fleuret]?”

Besnard’s conclusion was that fencing with a training weapon such as a foil removed a key element of danger from the sword play, leading to unnatural behavior by fencers during training sessions that would be suicidal in real combat.

By 1670 the foil was a prominent part of French fencing practices and it was heavily sportified as a popular amusement in the French royal court. A manual written by Philibert, Sr. de la Touche entitled Les vrays principes de l’espée seule (The True Principles of the Single Sword) clearly shows a shorter weapon than a standard rapier that is most certainly behaving as a foil.

After this the ‘court sword’, or smallsword, largely replaced the usage of rapiers until the smallsword itself was replaced by military sabres, and smallsword fencing with the foil became a social past time of European aristocrats. In the 18th century the Angelo family of fencers would continue to gamify the fencing styles until the 1880s when French fencing master Camille Prévost, Walter H. Pollock, and F.C. Grove created the basic conventions by which modern sport fencing utilizes in their book Fencing, with a complete bibliography of the art by Egerton Castle, M.A., F.S.A., which was published in London in 1889 as part of the Badminton Library. Lastly, Louis Rondelle would publish Foil and Sabre a Grammar of Fencing in detailed lessons for professor and pupil in 1892 which popularized the modern rules, too.

These rules were incorporated into the Fencing events that were a featured part of the Olympic Games in the summer of 1896, which had three separate fencing events; foil, masters foil and saber. Several fencing associations would then sprout up in countries around the world, until by 1909 there were many associations for participation in the Olympic games.

More biographical information about the historical French masters can be read at their respective pages.

- Henry de Saint-Didier

- François Dancie

- André des Borde

- Charles Besnard

English Rapier

Similar to the Brotherhood of St. Mark ( Marxbrüder) of the Holy Roman Empire, the Company of Maisters of the Science of Defence (more commonly called ‘Company of Masters’ for sake of brevity) was formed in England during the reign of King Henry VIII to regulate the teaching of fencing. The organization’s purpose was to ensure only quality instructors could teach in England by receiving a license but it also served to create a monopoly that protected the livelihoods of its membership. In this regard the Company of Masters was a form of a guild, and it had ranks similar to that which a guild awarded its members. These ranks were Scholar, Free Scholar, Provost and Maister. Many clubs in the present day HEMA community model their own ranking structures on those which the Company of Masters once used.

The Company of Masters eventually fell into obscurity after the passing of James I’s anti-monopoly laws but several of its members produced noteworthy fencing treatises covering a variety of weapons, including the rapier.

For the most part the English typically studied rapier fencing under Italian masters but there were a few rather original treatises either on or which include the weapon, which were written by English authors.

One of these is the The Private Schoole of Defence written by George Hale in 1614. Another, The Schoole of the Noble and Worthy Science of Defence, was written by Joseph Swetnam in 1617, who claimed to be the fencing instructor for Prince Henry Frederick.

In 1639 an anonymous writer going by the initials G.A. published Pallas Armata, the Gentlemans Armorie, which describes a method of rapier fencing based on the style of Salvator Fabris. It was translated into Dutch under the name Den Ridderlige og Adelige Fecht-Konstis (“The Chivalric and Noble Art of Fencing”) in 1646.

More information about some of these masters can be read at their Wiktenauer pages

PARTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

http://victorianfencingsociety.blogspot.com/2014/04/an-introduction-to-two-late-19th.html

Intersections: Actes Du 35e Congrès Annuel de la North American Society for Seventeenth-Century French Literature, Dartmouth College, 8-10 Mai 2003 Conference, Faith E. Beasley, Kathleen Wine, Gunter Narr Verlag, 2005

If you’d like to learn more information about historical fencing practices please check out our Learn HEMA page for a guide to learning about the historical weapon that interests you. You can also find more guides we’ve written about other topics at our Helpful Guides page.

Search

HEMA Resources Newsletter Signup

Signup to our newsletter for updates to new information, articles, products and more related to the exciting world of historical fencing!