Path of the Saber

“‘Henry Durie,’ said the Master, ‘Two words before I begin. You are a fencer, you can hold a foil; you little know what a change it makes to hold a sword!’”

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON, THE MASTER OF BALLANTRAE, 1889

For purposes of simplicity all manner of single edged blades will be discussed on this page, such as messers, dussacks, falchions, back-swords, broadswords, cutlasses and other single edged cavalry blades. We’re also including double edged blades which are used in a similar manner as the aforementioned single edged blades, as some varieties of them have two edged blades.

Although in the mind of the general public a saber (also spelled sabre) and a messer may be very different weapons, in actuality their usage largely relate to one another in some capacity. They are not so different as a long sword might be used in comparison to a rapier.

Consequently, for purposes of HEMA fencing it is useful to consider all of these single edged blades to be part of the same family of weapon. We believe it’s more effective to teach about sabers by simultaneously teaching about the evolution of the single edged blades in historical European martial arts than trying to isolate each subtype on their own page.

(While it is true that a rapier and a smallsword also have this similarity yet have their own respective pages on our site, we actually split those pages up because we think the sheer volume of information that one can learn about rapier fencing would have overshadowed the small sword information.

Also technically speaking these weapons are part of the ‘backsword’ family but nobody really searches for ‘backswords’ on Google, so in interest of helping others find what they are looking for we’re calling this page Path of the Sabre).

It is worth mentioning that the earliest recorded curved cavalry swords are considered to be Central Asian in origin, and historically many of these cultures primarily utilized curved swords. It is thought that through trade that curved sword designs spread into Europe, and as the design of these Central Asian swords evolved over time they became imported and imitated in Europe in various incarnations which we’ll talk something about later.

The Messer

mes are often used synonymously, messers are divided into two types:

- Lange Messer (“long knives”) are one-handed swords used by Bourgeoisie (middle-class civilians) for personal self-defence. They were about a meter long and may have evolved from the Bauernwehr (“peasant’s sidearm”). They are also known as Großes Messer (Great Knife).

- Kriegsmesser (“war knife”) are curved weapons up to 1.5m long, used with one or two hands, and normally wielded by professional warriors of the 14th to 16th century, such as the Landsknecht.

The messer was part of the curriculum of several Fechtbücher (fighting manuals) of the 14th and 15th centuries, often in the form of dussack plays, which is simply the Czech word for a messer-like weapon and became popular to refer to the messer as among the Germans in the 16th to 17th centuries. The same can be said about the falchion, which is the French word for this kind of weapon. It was also sometimes called a ‘hanger’ by historians, though this is a much later term that was meant to apply to cutlasses.

Historical examples of messers from this period can have differing types of hilting and blade types that could be common among certain ethnic groups at different periods of history, but regardless of these subtle differences any one of them is used similarly as another.

The Codex Wallerstein (Cod. I.6.4º.2) is a German fencing manual created sometime between the 1420s and 1470s. Images of it are frequently shown by documentaries when discussing historical medieval combat but it is not widely researched or studied by the HEMA community. It portrays techniques that are considered by some scholars to be part of the so-called ‘Gladiatoria tradition’ that existed at the same time that the Liechtenauer tradition did, and might represent a more common folk martial art style. Most of the plays are focused around teaching armored combat for judicial duels using various weapons, including the messer.

The Wallerstein manuscript came in the possession of Paulus Hector Mair in 1556 and was part of the collection of treatises he used for creating his own volumes.

The Liechtenauer tradition treatises often include material on the messer. In 1430 Johannes Lecküchner produced a manuscript dealing with the langes messer, Kunst des Messerfechtens (“The Art of Messer Fencing”). Two copies are known to still exist; the Codex Palatine German 430, completed in 1478, and the Cgm 582, completed on 19 January 1482.

- The Art of Swordsmanship by Hans Lecküchner

(Note: Lecküchner is sometimes confused with being the same individual as Johannes Liechtenauer, the founder of the Liechtenauer tradition. Lecküchner was a student of this tradition but he is not the same individual as Johannes Liechtenauer and the precise relationship between the two men is currently unknown.)

Nearly all of the Liechtenaeur tradition authors discuss the messer. This includes Hans Talhoffer, Paulus Kal, Paulus Hector Mair, Albrecht Dürer and Joachim Meyer. In the German Longsword section of the Path of the Longsword page we do a comprehensive breakdown of Liechtenaeur source material so please take a look at that list if you’re wanting more information.

Biographical information

The Basket-hilted sword

Often described just as a ‘broadsword’ or a ‘backsword’, the basket-hilted sword is a modern term for this type of weapon that developed in the 16th century, rising to popularity in the 17th century and remaining in widespread use throughout the 18th century, used especially by heavy cavalry up to the Napoleonic era.

Basket-hilted swords come in a few main types;

- Schiovona is named for the style used by the Balkan mercenaries who formed the bodyguard of the Doge of Venice, based on the fact that the guard consisted largely of the Schiavoni, Istrian and Dalmatian Slavs. It was widely recognizable for its “cat’s-head pommel” and distinctive handguard made up of many leaf-shaped brass or iron bars that was attached to the cross-bar and knucklebow rather than the pommel.

- Mortuary sword which was used after 1625 by cavalry during the English Civil War. This (usually) two-edged sword sported a half-basket hilt with a straight blade some 90–105 cm long. These hilts were often of very intricate sculpting and design. After the execution of King Charles I (1649), basket-hilted swords were made which depicted the face or death mask of the “martyred” king on the hilt. These swords came to be known as “mortuary swords”, and the term has been extended to refer to the entire type of Civil War–era broadswords by some 20th-century authors.

- Scottish broadsword, as it is popularly known today but natively as claidheamh beag or claybeg meaning “small sword” in Scottish Gaelic. This type was common among the clansmen during the Jacobite rebellions of the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

- Sinclair hilt, one of the earliest basket-hilt designs and was of south German origin. This style sported long quillons and an oval leather-wrapped grip. This style had a large triangular plate very similar to the ones used on main gauche daggers and was sometimes decorated with pierced hearts and diamonds.

- Walloon sword (épée wallone) or haudegen (hewing sword) was common in Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Scandinavia in the Thirty Years’ War and Baroque era. The hilts resembled the same pierced shell-guards, made during the same period known as Pappenheimer rapiers.

The back-sword was Oliver Cromwell’s weapon of choice; the one he owned is now held by the Royal Armouries, and displayed at the Tower of London.

The switch from rapier to basket-hilted swords for civilian and battlefield usage was anticipated by Englishman George Silver in his 1599 work, Paradoxes of Defence where he criticized the Italian methods of rapier fencing and later wrote Bref Instructions on my Paradoxes of Defence where he described his method of back-sword fencing, which he deemed to provide more adequate protection to the fencer and more battle-field utility as compared to a rapier. Interestingly Silver’s criticisms of the rapier would eventually be proven through the test of time as the rapier was eventually abandoned by militaries in favor of single edged swords, with the smallsword replacing civilian usage of the rapier.

“The exercising of weapons putteth away aches, griefs, and diseases, it increaseth strength and sharpeneth the wits, it giveth a perfect judgment, it expelleth melancholy, choleric, and evil conceits, it keepeth a man in breath, in perfect healthe, and long life.”

– GEORGE SILVER

In 1687 Sir William Hope published The Scots Fencing Master (the Complete Smallswordsman for which he is most well known for today, but he also published several other books until finally publishing in 1707 The New, Short and Easy Method of Fencing, or, the Art of the Broad and Small-Sword Rectified and Compendiz’d which depicted a radically different method of fencing compared to The Scots Fencing Master, intended to be used for self defense against even crowds using a unified theory for both weapons. He also notably published A Vindication of the True Art of Self Defence where he criticized dueling.

Colonel Donald McBane publishes The Expert Sword-Man’s Companion in 1728. Part autobiographical memoir and part fencing treatise on the Scottish broadsword, the work would influence HEMA reconstruction efforts in both the early 1900s and the early 2000s; you can learn more about that by reading this article.

In 1798 Charles Roworth published Art of Defense on Foot with the Broad Sword and Sabre, and then a 2nd edition that same year with additional expanded material and some textual changes. The manual covered the usage of the spadroon, infantry saber, Scottish basket-hilted broadsword, cutlass, and cavalry sabers when used on foot. Roworth said that his style blended Scottish and Austrian methods of fencing together into one. The book was highly influential for its time. A third edition in 1804 included material contributed by John Taylor and this sometimes results in people confusing John Taylor as being the author of the third edition. A fourth edition was printed in 1824. This manual is commonly used among HEMA sabre fencers today.

Henry Angelo would also publish in 1798 a book on sabre fencing while mounted on horseback, Hungarian & Highland Broad Sword . Many of the illustrations depict Angelo himself.

In 1890 Rowland Allanson-Winn, 5th Baron Headley co-authored with C. Phillipps-Wolley, the fencing instructional manual Broad-sword and Singlestick. It also included sections on the usage of the quarter-staff, bayonet, cudgel, shillelagh walking-stick, and umbrella.

You can read more information about some of these authors at their biographical pages.

The Cutlass

The word cutlass developed from a 17th-century English variation of coutelas, a 16th-century French word for a machete-like blade (the modern French for “knife”, in general, is “couteau”; the word was often spelled “cuttoe” in 17th and 18th century English). The French word is itself a corruption of the Italian coltellaccio or cortelazo, meaning “large knife”, a short, broad-bladed sabre popular in Italy during the 16th century. The word comes from coltello, “knife”, derived ultimately from Latin cultellus meaning “small knife.”

The Cutlass is popularly associated with naval warfare, possibly due to its duel usage as a machete for cutting ropes on board a ship.

As mentioned previously Henry Angelo’s Art of Defense on Foot with the Broad Sword and Sabre (1798) covers usage of a cutlass.

The Cavalry Sabre

It became popular in the 19th century for Western militaries to adopt the usage of cross-hilted sabres that imitated the style of Mamluk warriors; these sabres are referred to as a Mameluke sword.

In 1804 M.J. de St. Martin published in French The Art of Fencing Reduced to True Principles which covered material for the smallsword and the sabre.

A Spanish manual of sabre fencing was written by Simon de Frias in 1809, titled Tratado Elemental de la Destreza del Sable. It describes a method of sabre fencing utilizing principles from the Destreza rapier tradition.

One of the most influential authors was Henry Charles Angelo the Younger who published Infantry Sword Exercise in 1845.

In 1847 Philipp Müller published in Germany Theoretical and Applied Introduction to Swordsmanship on the usage of the military sabre.

In 1862 Jaime Merelo y Casademunt published Esgrima del Sable Español, 1862 in Spanish.

In 1880 John Musgrave Waite published a book entitled, Lessons in Sabre, Singlestick, Sabre and Bayonet, and Sword Feats. The book is rather notable to modern day HEMA fencers as it includes some information on ‘sword feats’, which were displays of test cuts done against animal carcasses and soft lead objects. These feats were done using sabres purpose-built for the task, and where sometimes heavier than average sabres would be.

In 1887 Manuel d’Escrime was written by Luis Rondelle for the French War Ministry, and he would also publish Foil and Sabre: A Grammar of Fencing in Detailed Lessons for Professor and Pupil in 1892.

One of Henry Charles Angelo’s students was Alfred Hutton, who became a famous fencer and author in his own right. Hutton published Cold Steel in 1889 that described a method of sabre fencing he had learned based off English broadsword.

He wrote a book on bayonets, published as Fixed Bayonets, in 1890. Hutton then wrote Old Sword-Play in 1892 that discussed usage of older weapons such as the great sword (called the ‘long sword’ by him), rapier and dagger, broadsword and buckler.

Hutton can be considered the first person to attempt to revive the historical European martial arts of the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance and his work would influence the development of stage fencing into the theatrical scene. You can learn more about his contributions to the revival of HEMA in the 20th century by reading our article, History of the Modern HEMA Movement.

- Cold Steel: The Art of Fencing with the Sabre

In 1895 Cavaliere Ferdinando Masiello of Florence would develop a new version of infantry sabre manual for the British military, the Infantry Sword Exercise 1895. It is believed that this version of sabre fencing was inspired by the theory and methods of Milanese fencing master Giuseppe Radaelli (1833 – 1882).

In 1905 Leopold van Humbeek published a book of sabre fencing entitled Handleiding voor het Sabelschermen which he claimed is based on an Italian style.

The very last military saber book to be created for actual military usage is Saber Exercise Manual – 1914. Written by then George S. Patton, who was then a Lieutenant and not yet the famous World War II General he would become, it described a method of thrusting oriented saber combat using the Model 1913 Cavalry Sword, based on the British Pattern 1908 and 1912 cavalry sabers.

Patton would later write several articles from 1913 to 1917 explaining the idea behind his radical redesign of the saber for the cavalry charge. He also produced ‘Diary of the Instructor in Swordsmanship‘ which expanded on material in the 1914 field manual.

You can read more biographical information about some these masters at their respective pages.

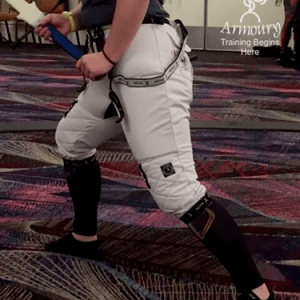

Learning Sabre

There are some books created by present day authors within the HEMA community that seek to make sabre fencing more accessible. Here are some of them.

- The Polish Saber

- Hungarian Hussar Sabre and Fokos Fencing

PARTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

Henry Angelo’s Art of Self Defence on Foot with the Broadsword and Sabre, Second Edition 1798 with foreword by Nick Thomas, http://swordfight.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Art-of-Defence-on-Foot-Second-Edition.pdf

1845 Infantry Sword Exercise http://www.fioredeiliberi.org/topics/sources/1845-infantry-sword-exercise.pdf

Broadsword and Single Stick

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/31214/31214-h/31214-h.htm

John Musgrave Waite

http://www.fioredeiliberi.org/topics/sources/Lessons_in_Sabre-Waite-1880.pdf

Radaellian Scholar http://radaellianscholar.blogspot.com/2016/12/who-is-giuseppe-radaelli.html

*****

If you’d like to learn more information about historical fencing practices please check out our Learn HEMA page for a guide to learning about the historical weapon that interests you. You can also find more guides we’ve written about other topics at our Helpful Guides page.

Search

HEMA Resources Newsletter Signup

Signup to our newsletter for updates to new information, articles, products and more related to the exciting world of historical fencing!

HEMA Resources Facebook Community

Recommended HEMA Products

Nearest HEMA Clubs to You