The bulk of Historical European martial artists focus on martial art practices of the Late Middle Ages and younger as these are well sourced, with older practices that are less well documented rarely discussed. So we thought that we might discuss the topic as a general overview to provide some information. In this article we will briefly discuss older pre-Late Middle Ages martial arts practices of Europeans.

The earliest known European martial arts dates back to the traditions of ancient Greece, and these entailed wrestling, boxing, and Pankration which developed and formed part of the Ancient Olympic Games (Green & Svinth, 2010). The early periods in Europe also had the Roman combat sport of gladiatorial combat. This article will undertake a brief review of the ancient European arts practices that are generally classified as from the classical antiquity period notable for groups such as the ancient Greek, Spartans, and Romans.

The primitive period of martial arts

Weapons such as spears, bows, slings and clubs appear in ancient artwork appearing in present day Egypt, and even in present day Vietnam artwork that is as old as 2879 BCE describe depict warriors using sword, stick, bow, and spears (Pawluk, Zukow, 2011). These weapons are common to all primitive human cultures. During the European Bronze Age (c. 3200–600 BC) the development of metal bladed weapons such as swords, spears, axes and unique Greek kopis. During the Iron Age there came the development of the double-edged leaf-shaped bladed xiphos, the predecessor of the Roman spatha sword.

That said, wielding a spear with a large shield was the predominant military arms used for warfare for many centuries of conflict, with formations such as phalanxes. This practice was used by all ancient European peoples and Julius Caesar notes in his journals that he witnessed even the Celtic people of Gaul utilize this method of warfare (Ellis, 1998).

While we know little about the specific techniques used in Bronze age martial arts, through analysis of surviving weapons from this period researchers have been able to gather some information. For example we have a general idea of what kind of techniques were used for parrying with swords based on sustained damage to surviving swords when compared to contemporary reproductions used by HEMA practitioners.

Prehistoric Swords

Ever since man stood up straight for the first time, he realized that he would need tools to get things done. Tools would help him accomplish things he couldn’t do on her own, and they would make other tasks easier. He also realized that the world was dangerous, and he would need to protect his home and family from things that could harm them. If he couldn’t defend his homestead based on his brawn and brain alone, he would need some help. Of course, the best help is something sharp that could pierce an animal or human foe. For this reason they started sharpening rocks into blades. Soon the blades were formed into crude short daggers.

The earliest tools or weapons that could be considered “swords” first appeared in the Bronze Age. A weapon was found in Turkey that turned out to be from 3000 B.C. (that’s over 5000 years old!), and it was made of bronze. This weapon is currently on display in a facility in the Vatican. Bronze is not as strong as steel, which became the preferred material for swords later. To make the weapons as strong as possible, they were shorter than future swords.

The classical antiquities period of European martial arts practices

Ancient Greek Wrestling

Palé (Greek wrestling) formed part of the ancient European martial arts that was the most popularly organized sport in the Ancient Greece (Green & Svinth, 2010). The Ancient Greek wrestling was highly regarded to be the best expression of strength from the competitions that were held at the time, and it became the first competition which was not a footrace to be added in the Olympic Games in 708 B.C. The competition adopted the format of the elimination-tournament style that would have one wrestler being crowned the victor, and it also formed part of the sports making up the pentathlon (Green & Svinth, 2010).

The Ancient Greek wrestling adopted the format where a point would be scored in the event that one of the players touches the ground with their back, hip, or shoulder, and three points had to be scored for purposes of crowning victory to a certain player. The player could also concede defeat in the event that they are forced out of the wrestling area or due to submission-hold. Part of the important popular position that was being used by the contestants at the time entailed lying on their abdomen and using the back to strangle the opponent. The other tactic entailed the athlete at the bottom trying to grasp the arm of the opponent at the top to try and turn them onto their back as the one on top would be trying to complete the choke and to avoid being rolled over (Green & Svinth, 2010).

One of the earliest surviving European martial arts manuals is the Papyrus Oxyrhynchus III 466 (P. Oxy. III,466). Believed to date to the 2nd century this papyrus contains fragments of the original larger work that provides instructions for wrestling holds and grips.

Ancient Greek Boxing

Boxing was largely referred to as πυγμαχία pygmachia, in Ancient Greek which means “fist fighting”. This martial practice dates back to the 8th century B.C. where it was practiced in different social contexts among the varied cities in the Greek states (Dasgupta, 2004). The origin of boxing in Greece are obscured with much of the surviving information based on legends, making them difficult to determine the authenticity of and has made it difficult to obtain the exact origins of Greek boxing. It has also been difficult to reconstruct the customs, rules, and the other historical basis that surrounds the activity of boxing.

There is some evidence to suggest the boxers utilized defensive equipment to protect the knuckles, similar in style and construction as modern day boxing handwraps. Ox hide stripped into thongs were wrapped numerous times around the hands and knuckles. Additionally punching bags were used by the fighters during conditioning training, which modern day boxers still do.

Pankration

Pankration is derived from the Greek word meaning “all of power” from πᾶν (pan) “all” and κράτος (kratos) “strength, might, power”.

Pankration was introduced in 648 B.C. as a sporting event in the Greek Olympic Games, and involved competitors using a combination of both wrestling and striking techniques using the hands and legs, and would likely resemble modern mixed martial arts matches. The matches are described as rather brutal, with very few rules; uniquely it allowed eye gouging and biting, and matches would continue in an uninterrupted manner until one fighter would submit by raising their index finger (Green & Svinth, 2010).

The form of Pankration we discuss here should not be confused for Modern Pankration, (sometimes called Neo-Pankration) which is a contemporary grappling martial art inspired by the stories from antiquity that was developed by Jim Arvanitis in 1969.

The martial art of Pankration as it was practiced in the historical antiquity was presented as a sporting event that had the opponents use the combined techniques of both boxing (πυγμαχία pygmachia, “fist fighting”) and wrestling. The sport was known in the ancient times for its ferocity with the allowances of the tactics such as eye gouging and the knees to the head, but the extreme nature of the tactics being applied resulted in majority of the instances where men in the arena who were involved in the event died from their injuries, thus making it hard for the judges to determine the victor (Green & Svinth, 2010). The competitors were referred to as the Pankratiasts, and they were highly skilled in the hand-to-hand combat which helped them to be extremely effective through the application of the acts such as the chokes, takedowns, and the joint locks.

Aside from being practiced as a sporting event, pankration was also a martial art utilized by Greek soldiers for warfare, notably the Athenians and Spartans (Green & Svinth, 2010).

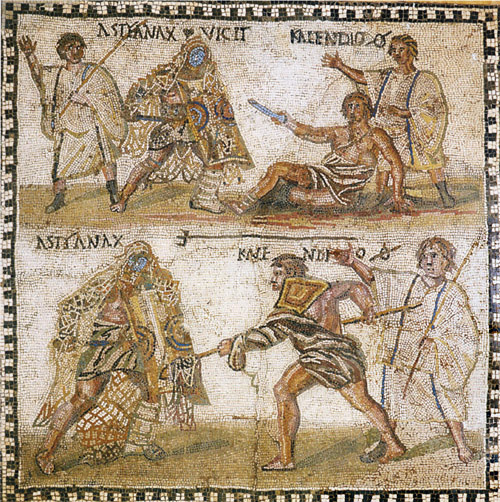

Roman Gladiatorial combat

Gladiatorial combat forms an ancient European martial art that was produced by the Romans as a public spectacle. The sport entailed an armed combatant event designed to entertain audiences in the Roman Republic, and later Roman Empire, through the use of the violent confrontations with the other gladiators, condemned criminals, and the wild animals (Green & Svinth, 2010). The origin of gladiatorial combat is widely open to debate, and although the gladiator games had lasted for about a thousand years with its peak in the 1st century B.C. and 2nd century A.D., its decline was marked by the adoption of Christianity as the state church for the Roman Empire in the early 5th century (Green & Svinth, 2010).

The gladiators and their fighting styles were mainly based after Rome’s ancient enemies. For instance, the ones who were named the Samnite were the most popular for a time, and were characterized by being heavily armed and elegantly helmed (Green & Svinth, 2010) while the Retiarius was modeled on a fisherman fighting with a net and a trident. However, the latter period had varied fantasy types of gladiators introduced, such as the introduction of gladiators who were bareheaded, those armored only on one arm and shoulder, and so on. There were also types of gladiators who fought from chariots or from horseback.

An excellent overview of the different types of Roman gladiators and their weapons is discussed by Matt Easton in the following video,

Middle Ages martial art practices

Much like the classical period there is very little information about the martial art practices of the Middle Ages. Most of what we know comes from depictions of combat from tapestries and small amounts of written documentation. For example according to the “Tacktica” of Emperor Leon the Wise, he suggested his generals to train their soldiers with wooden swords or wooden sticks or cane ( to avoid serious injuries ) and using shields and armors or unarmoured. Furthermore he suggested his generals to let their soldiers to do skirmishes or duels with the above equipment.

There are also numerous Norse (Icelandic) Sagas that feature descriptions of battles both large and small, and from these stories some concept of how weapons were used during this period can be gleamed.

Likewise although we have many surviving manuscripts and tapestries that describe early medieval European combat and warfare engaged in by the Goths, the Franks, the Anglo-Saxons and even latter Crusaders, we know very little about the specific techniques they used. The majority of what we know is about the equipment of soldiers and the kinds of tactics the armies used as a whole unit, with little information about the specific techniques used by individual soldiers surviving to present day.

Despite this difficulty HEMA martial artist instructor Roland Warzecha has spent many years researching these older styles of combat and constructed his own interpretation of the material based on small amounts of this surviving documentation, such as pictorial depictions on wall paintings and recorded stories, as well as experimental archaeology in regard to exploring the ergonomic properties of reproduced arms.

Conclusion

Although very little information has survived from the pre-Late Middle Ages periods that details the specific techniques of ancient European martial artists and much of what we know are accounts about the kinds of weapons, armor and rules for combat sports like Pankration existed, these arts still form an important connection to the modern HEMA movement. These arts formed the foundation for the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance martial traditions studied by contemporary historical European martial artists. So although the majority of what was practiced has been lost and forgotten, nevertheless they contributed to the development of the styles we study today.

References

Dasgupta, S. (June-September 2004). An Inheritance from the British: The Indian Boxing Story. Routledge, 21(3), 433-451.

Actaeon attacked by his hounds. Detail from a Lucanian red-figure nestoris, Metaponto, ca. 390-380 BC. From the Basilicata. © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons. [Online] Accessed at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Death_Actaeon_BM_VaseF176.jpg

Ellis, Peter Berresford (1998). The Celts: A History. Caroll & Graf. pp. 60–63

Iwona Czerwinska Pawluk and Walery Zukow (2011). Humanities dimension of physiotherapy, rehabilitation, nursing and public health. p. 21

Greek Wrestling, Wikipedia [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_wrestling

Ancient Greek boxing, Wikipedia [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_boxing

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 466, Wikipedia [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Papyrus_Oxyrhynchus_466

Green, T.A., & Svinth, J.R. (2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. California: ABC-CLIO Publishing .

Retiarius,Wikipedia [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Retiarius

Samnite, Wikipedia [Online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samnite_(gladiator_type)

Mosaic at the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid showing a retiarius (net-fighter) named Kalendio fighting a secutor named Astyanax. [Online] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Astyanax_vs_Kalendio_mosaic.jpg

Svinth, J. (2002). A Chronological History of the Martial Arts and Combative Sports. Electronic Journals of Martial Arts and Sciences. Retrieved from https://ejmas.com/kronos/

***

If you’d like to learn more information about historical fencing practices please check out our Learn HEMA page for a guide to learning about the historical weapon that interests you. You can also find more guides we’ve written about other topics at our Helpful Guides page. You can also join the conversation at our forums or our Facebook Group community.