‘Forged in Fire‘ is an television series produced for the United States based cable television History Channel and has become popular, with its episodes gaining many millions of views, to the point that even clips of the show receive enormous attention on video sharing sites like YouTube. Unfortunately, while the show has helped inspire and popularize knife and sword smithing the same way that previous shows such as the YouTube channel AWE Me’s Man At Arms did, ‘Forged in Fire‘ is problematic in that it advertises itself as making tests based in realism and that its producers / judges are experts in the types of swords which are forged and tested on the show. They actually are not.

The History Channel TV Series Forged In Fire is a bad representative of historical swordsmanship and blade forging. The scope of this article is to explain the problems with the Forged in Fire television show, and how it can be improved to do better at what it seeks to do; educate the public about accurate swordsmanship, sword blade forging and sword history in a way that is entertaining.

Many of these criticisms can also be applied to other History Channel shows featuring the producers of Forged in Fire, such as History’s Deadliest Warrior series.

Criticism #1: Doug Marcaida is Not an Expert Swordsman

Doug Marcaida simply is not an expert in the usage of any of the swords that are typically tested on the show. He frequently mishandles the swords and then blames the smiths for his own incompetence. This misleads the audience into thinking the smith is at fault.

For what it is worth, Doug Marcaida claims to be an expert martial artist in the particular art that he trains in, which is Escrima / Arnis. Escrima has its origins in combining the historical knife and sword fighting traditions of Polynesian peoples with Spanish military sabre and stick-fighting techniques. This style developed during the Spanish Empire’s colonization of the Philippines starting in the 16th century that lasted until 1898. An important thing to understand is that Escrima is primarily practiced with sticks, not swords or daggers, and free sparring with blades, even blunted ones, is almost never done by Escrima practitioners. Furthermore the type of blades used in Escrima are rarely longer than a long dagger. While Escrima can hypothetically be considered a style that incorporates bladed weaponry, the reality is that practitioners overwhelmingly train using sticks, not edged weapons.

This means that even experts in Escrima such as Doug Marcaida have little practical experience with weapons longer than a dagger in a fight situation, let alone for test cutting. Mainly the fighting style techniques of Escrima are optimized for stick fighting. This is important because it has influenced the type of grips used in Escrima, the precise way that the weapons are held. The Escrima hand grip techniques are meant for a round handle and striking area such as featured on rattan sticks, not for the kinds of handles and blades frequently appearing on the swords Marcaida test cuts on the ‘Forged in Fire‘ television show. Furthermore because the sticks do not have an edge, practitioners of Escrima often do not optimize their techniques for striking in a way that is optimal for a bladed weapon, especially the types of weapons that require two-handed gripping positions such as long-swords, great swords (mistakenly referred to as ‘claymores’ in the show by the so-called “weapon experts”) and even one-handed broad swords.

On top this, Doug Marcaida frequently demonstrates techniques with one handed swords that implies he doesn’t really understand how to do blade cuts even within Escrima. We will talk more about this later on in this article.

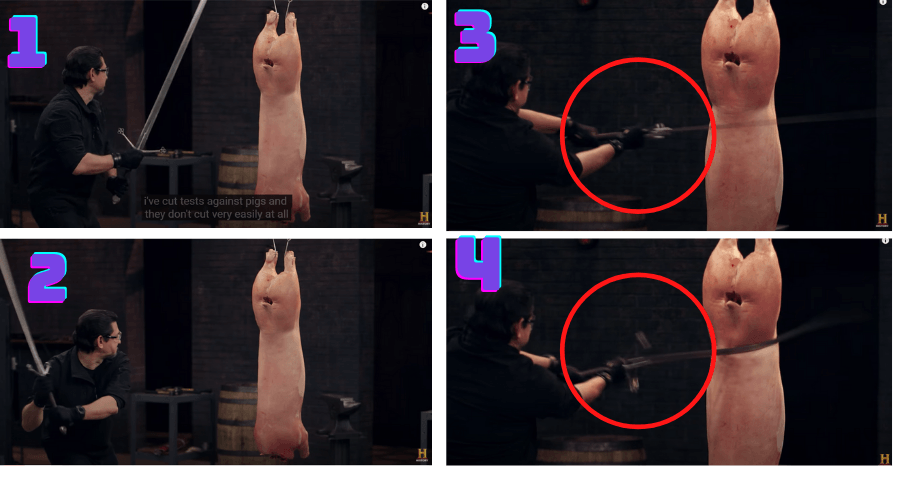

As Escrima is primarily trained with sticks and not edged weapons, and Marcaida claims to have no other martial art background, Marcaida simply has no training in how to handle the types of edged weapons that he cuts with on the show. This is why his body mechanics are poorly aligned for making cuts with these weapons. Every time that Marcaida strikes flat with the blade of a sword and then claims it is because the edge was “dull”, what often actually happened is that Marcaida did not have his body alignment correct for making these cuts through pig carcasses or sand-bags, or what-have-you. This can be easily seen in the videos by examining Marcaida’s knuckle placement when he makes contact with the target; his knuckles are never aligned with the edge of the blade after making contact, and sometimes not even before making contact.

Granted, Marcaida is not the only person who makes these mistakes; so do the other judges when they do destruction testing with the swords, too. But Marcaida is the only producer of the show who advertises himself as an edged weapon martial arts expert when he is actually only a stick fighting expert.

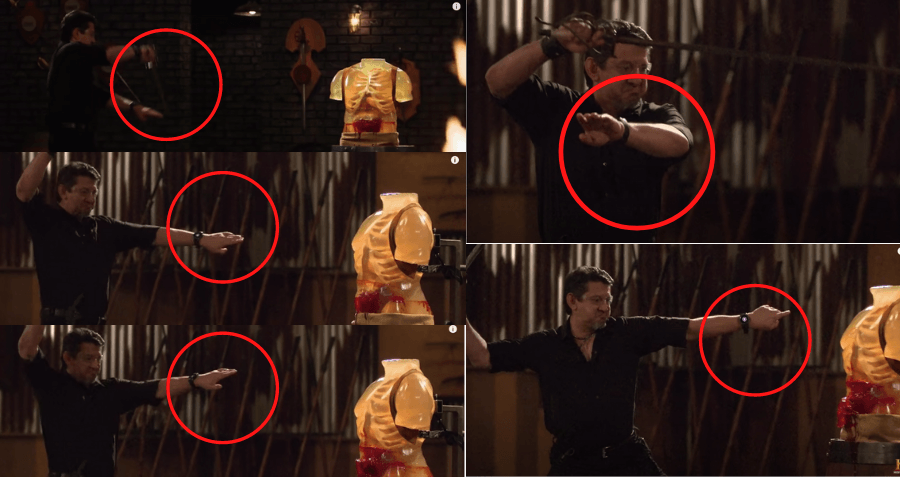

Here is a clip from the show that starts with a few failed cuts Marcaida made due to his poor body mechanics.

Firstly, just because this needs to be said, this episode did not have any “claymores” in it; a claymore is actually a type of one-handed broadsword. Furthermore what they call a “claymore” in this video is actually more properly classified as a long sword. So the entire “historical background” information section about “claymores” is just 100% mistaken about everything, including the part about William Wallace wielding a large two-handed sword in battle.

William Wallace lived almost a century before great swords were in usage on European battlefields, and the large great sword attributed to him (the one held at the National Wallace Monument) is well understood today to be a forgery created hundreds of years after his death, which explains why it has anachronistic elements. The development of long two-handed swords in Europe coincides with the diminished usage of the shield as a secondary weapon due to the development of steel plate armour; William Wallace died in 1305; complete suits of steel plate armor did not come into usage until 1420, and great swords primarily saw battlefield usage during the Italian Wars that started in 1494.

Additionally the design of sword used in the 1995 Mel Gibson movie ‘Braveheart’ is historically inaccurate; no real two-handed sword ever looked like the one featured in the movie; the closest thing to it would be a Renaissance era montante that is missing the horned prongs above the ricasso. This type of sword first appeared over a century after William Wallace died; in terms of ridiculousness, giving William Wallace a greatsword would be like making a movie where Billy the Kid used a Colt 1911 as his pistol.

No authentic two-handed sword from this time period would ever look like this sword from the Braveheart movie. The leather wrapped ricasso defeats the entire point of having a ricasso and would interfere with binding work techniques since it is missing the prongs a montante should possess. Furthermore the blade lacks a fuller.

The design of longsword used in this episode of Forged in Fire is stated as being 55 inches in total, which is within the length for a longsword classification. Not stated in the episode is that this sword design is commonly used on mass produced decorative wall hanger sword-like objects marketed as “claymores” by primarily Asian forges, produced as non-functional stainless steel swords for sword enthusiasts and collectors. These mass produced swords themselves are (inaccurate) replicas of a surviving sword believed to date to the 16th century that is currently held in the collection of National War Museum in Edinburgh, Scotland, and sports two decorative quatrefoil on the ends of the pronged crossguard. This sword, which is labeled as piece H.LA 105, has been mistakenly labeled as a ‘claymore’ by past curators of the museum, but it would more properly be called a claidheamh dà làimh; which was the Gaelic label for what we refer to today as longswords.

H.LA 105 from the National War Museum in Edinburgh, Scotland, erroneously labeled a ‘claymore’ by past curators. This is the model for many cheap replicas of ‘claymores’ sold in magazines and internet sites.

The word ‘claymore’ is a bastardization of claidheamh mòr, which was a label for an altogether different category of sword blade type appearing much later, a one-handed basket-hilted broadsword used in the 17th century. The classification error of ‘claymore‘ to a longsword stems to a mistake made in the 1911 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica; this fact is well known to military weapon historians, which the show very obviously does not have among its producers (they have made this mistake several times over the course of the show’s production). Instead the show producers are using the word ‘claymore’ because it is popular for the Asian sword market to do so. This error demonstrates the Forged in Fire producers have little genuine understanding of European weapons history.

It must be said that while replicas of the longsword held in the National War Museum are popularly produced as replicas, the sword hilt design itself is considered to be rather unique and rare, and not representative of what was common to Scottish longswords of the 16th century. It may have actually been a parade sword not intended for use in battle at all.

You can learn more about long swords and why they are classified this way in our related article, ‘What is a Longsword? An Evaluation of the Historical Context‘.

Secondly, we have analysis of how Marcaida swings the longsword that demonstrates he is doing so incorrectly.

To explain it simply, Marcaida swings a longsword as if it were a baseball bat. This is an incorrect way to cut with a longsword, as the physical characteristics of a longsword are different than that of a baseball bat, which is a spherical blunt baton weighted toward its end, and designed to knock leather balls into the air. A sword by contrast is an edged weapon designed to cut and pierce human beings, and its handling characteristics are very different. If you do not have proper alignment of your knuckles, your arms, your shoulders and your legs then you will not be able to cut a target such as a pig carcass very well. The times when Marcaida successfully cuts through a target like this seem to be more of a fluke than the result of him actually knowing what he is doing.

We know Marcaida does not truly understand how to cut with a longsword because of the way he grips these swords and the position he takes before striking.

As there are several mistakes Marcaida makes, let us dissect each of them.

Marcaida uses a grip position with his forward dominant hand (the right hand) that grabs the sword handle as if it was a hammer. We know this is the case because when he fails to cut through a target, the blade turns and slaps against the target with the flat. This happens in both episode examples shown in the above YouTube clip.

His body position and arm position generally remains consistent at the point of impact; it is only the sword that turns, and we know this because we can see the crossbar and blade turn together. This is a consequence of poor gripping technique.

One of the reasons the blades turn like this is because he is not gripping with the bottom two fingers of his front hand (the pinky and the ring finger). Were he gripping with these two fingers, the blade would not turn like this so easily when he fails to cut through the target, even if his edge alignment was slightly off. The reason he loses control and the flat of his blade goes hurling toward the pig carcass is because he is trying to use his right hand’s index finger as the fulcrum; this is a very weak position in contrast to the bottom two fingers of the right hand when gripping a rounded rectangular handle (which is what swords use and sticks do not). Marcaida therefore has difficulty keeping the edge of the blade on the target when he makes contact, and loses control of the blade. When the flat of his blade slaps the front of the target, that is what we are seeing — Marcaida is losing control of the blade in his right hand as the force overpowers his index finger being used as a fulcrum point when contact is made with a target.

To put this simply, even if the sword blades he tested on the pig were completely dull edged, were he gripping the sword properly to start with he would not end up losing control of the blade upon making contact, having the handle turn in his right hand, allowing the blade to slap with its flat. An expert swordsmen would have maintained control of the blade.

The reason Marcaida is using such an incorrect grip is probably because using the forefinger as the fulcrum point of a grip is a very common thing in Escrima stick and knife fighting. The Escrima fighters often get away with this because the weapons they primarily use are sticks not designed to cut through objects — this means ‘edge alignment’ is not really an aspect of their normal training so they do not develop it. While hypothetically Escrima incorporates edged weapons, the system is designed so that stick techniques can be used for edged weapons; this means an Escrima practitioner uses a knife or short sword the same way they use a stick. Therefore they primarily practice with sticks, not swords, since sticks are safer to wield in sparring and striking practice. So the bad habits they develop while stick fighting often carry over into their edged weapon work.

Additionally the short length of the knives used in Escrima don’t generally cause an issue when the forefinger is used as the fulcrum point, however in a larger, heavier blade using the forefingers as a fulcrum is a mistake; you want to use your bottom two fingers as the fulcrum as this gives you better control. This is not something unique to European swordsmanship; it is also an aspect of Japanese swordsmanship, too (this is why the historical Japanese yubitsume corporal punishment still practiced among Yakuza gangsters starts with amputating digits from the pinky finger; this makes it so you cannot properly wield a sword anymore.)

Therefore, by not gripping European longswords properly this also means Marcaida is not familiar with Japanese swordsmanship, either. This is one of the things that proves Marcaida has no training in swordsmanship at all despite his claims to be an ‘edged weapon expert’.

What Marcaida does with his left arm is also mistaken. While Marcaida correctly grips with his left hand just above the pommel (a more optimal hand position for generating power to cut through an object such as a pig carcass, in contrast to gripping the pommel which is more useful for binding work in longsword fencing) he does not keep his elbows close enough to his body to properly leverage his skeletal frame for keeping the blade at a stable and consistent angle when he makes contact. This, too, contributes to why he often cannot make a cut he should otherwise be able to make. He simply does not have a strong position when he makes contact with the targets and he loses control of the sword blade at the moment of contact with his targets.

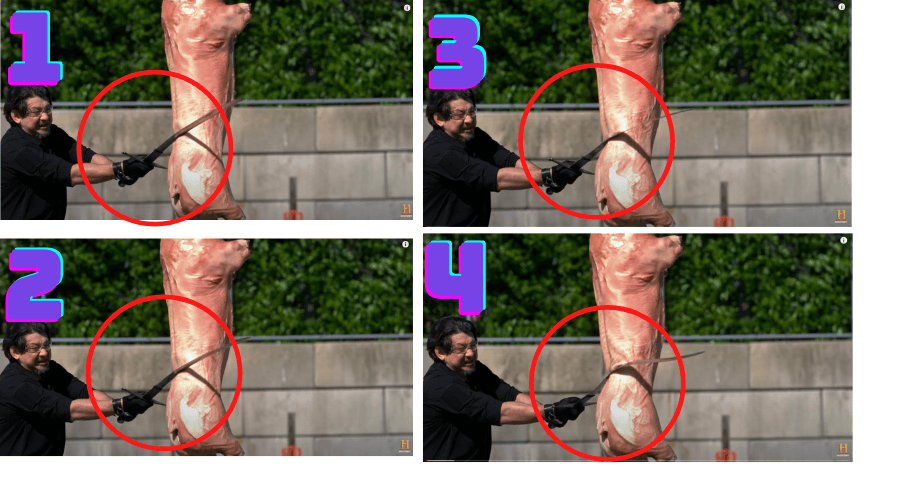

Marcaida starting position in frame 1 ; he then pulls the sword back and away from his center of mass in frame 2; he swings the sword while taking a step forward with his right foot and bringing his left elbow up to his shoulder length in frame 3; making contact in frame 4, he has poor edge alignment and a weak hand position, resulting in losing control of the blade.

The result is that the blade rotates in his right hand as he loses control of the fulcrum, as his index finger is overpowered by the force resisted against the blade by the pig carcass. This causes the sword to roll, the flat of the edge hitting the pig carcass.

If I had to guess, Marcaida performs better with swords that are blade heavy, where the problems of using the forefinger of the dominant hand as the fulcrum point are lessened by the sword naturally doing more of the cutting work for the swordsman by better stabilizing the force transferred to the target. However a sword that is blade heavy can make for a poorer combat weapon, as it turns slower (making it less effective in the bind for defensive fencing work) and is more prone to tire the swordsman out faster. Another factor to consider is that due to the bending test performed on the show, smiths who want to do well on this part of the test tend to make their blades with a thinner cross section, as this is a necessary aspect of the blade geometry to perform the best in this bending test. While a sword with a thinner blade will usually cut objects better than a thicker blade will, the drawback with a thinner blade is that you must have excellent edge alignment control (which as explained previously in this article, Marcaida lacks due to using his right hand’s index finger as the fulcrum point for his grips). If you strike a target with a thin blade but have imperfect edge alignment, it is easier to fail.

Due to the usage of jump cuts, the full video of how Marcaida moves his body when performing a cut with a two handed sword is not shown; we frequently have a shot of him starting his cut and then jump to him making contact with the target, taken at a closer framed shot. Yet Marcaida’s body alignment in these two sequences implies he is trying to do the work primarily with his triceps and shoulders, and a shift of weight with his footwork at the end of his swing to drop his body weight into the strike. This can be deduced because the starting position of his cuts is far from his body, with the sword held far from his center of mass. This is contrast to holding the sword close to his body (such as resting over his shoulder in a position such as Posta di Donna / Zornhut) where his body mass itself can be used to propel the sword at the target, giving him substantially more power than what his triceps are able to generate. Even though he sinks his weight into his strike at the end of the motion just before making contact, because he did not generate the maximum amount of speed he could swing at, he often fails to consistently generate enough force to make the cuts he otherwise could do with the sword he is wielding.

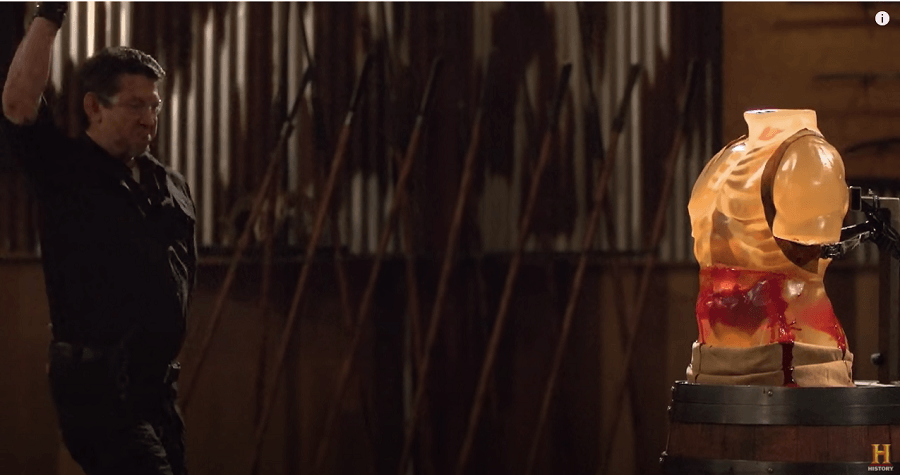

So far, these criticisms has been focused on how Marcaida uses two handed swords. Yet he also doesn’t know how to use one handed swords, either, such as rapiers. At around the 4 minute mark into the clip below, he demonstrates he knows nothing about how to use a rapier up to and including throwing his left hand in front of his body and then pulling it back as he performs a cut with his right hand; this is not a cutting technique in any rapier treatise, and during a real sword fight would result in his left arm getting stabbed as he has given it to his opponent as an obvious target.

Marcaida simply has no idea how to fight with a one handed sword, and this move would not be good during a stick fight, either.

Doug Marcaida exposes his face to the enemy. This is not how you thrust with a rapier.

Doug Marcaida exposing his entire torso and face to the enemy while preparing to make a wide telegraphed overhead cut in close range to the target, the sword raised behind his head. This is not how you cut with a rapier (or any one-handed sword for that matter).

Doug Marcaida offering his hand to the enemy as a target while demonstrating he has no idea how to perform any type of one handed sword cut. At this range to the opponent, the sword should always be in front of you, in a position to defend against any potential counter attacks.

It was written earlier at the start of this article that Doug Marcaida does not seem to understand how to perform one-handed sword cuts even within the art of Escrima. When he performs cuts with a one-handed sword he often presents his hand or face to his enemy as a target while he is in close range to his opponent and preparing to strike, throwing the weapon behind him (and where it can no longer defend him). This calls into question his exact level of expertise with functional weapons training, as this is something that would get a person injured in stick fighting and killed in an actual fight with bladed weapons.

Beyond these observations, all of the important characteristics of a rapier that make it an excellent weapon are rendered pointless by how incorrectly he wields the “rapiers” in this episode. He cannot possibly judge if they are a good weapon or not, as he doesn’t know how to use a rapier. If he doesn’t know how to use a rapier then he cannot assess the qualities a good rapier should have.

Many different types of edged weapons have slightly different ways to cut optimally with them, but the general principles of “don’t give your opponent easy targets”, “grip the sword handle properly” and “don’t throw your opposite hand in front of your body” apply to all of these weapons. Marcaida makes these mistakes routinely in the episodes, as does his brother in the episodes he performed test cuts for him due to Marcaida’s broken arm.

Simply put, Doug Marcaida does not know how to use the edged weapons featured in the show Forged in Fire, and therefore cannot accurately judge if they are capable of using their intended techniques. This can give viewers at home the impression there was something wrong with the swords he failed to cut with, while also misinforming viewers on how these weapons are supposed to be used.

Criticism #2: David Baker Is Not an Expert Sword Historian Yet Is Portrayed as One

David Baker is not an expert on historical European weapons and frequently makes mistakes no person with even a modest amount of knowledge about these weapons would make. A notable example is the show producers calling longswords a ‘claymore’ but there are numerous other mistakes that stand out throughout the show’s many seasons. Were Baker actually deeply educated about swords and their history he would not make these kinds of mistakes.

David Baker’s actual background is as a self-trained prop maker for the Hollywood film industry; specifically, the films Beowulf (2007), Dragonball Evolution (2009), and Jonah Hex (2010) . Prop weapons have entirely different needs than historical weapons do. Mainly, they need to look good for closeup shots and not easily break during stunt work, as a broken weapon would interrupt filming. This means that prop weapons tend to be more durable (and heavier) than real actual swords would be. Additionally, since almost no one in the Hollywood stage fighting industry has studied historical swordsmanship, the techniques these prop weapons use in fight choreography are very different than what their historical counterparts would be required to perform. Baker therefore only knows what qualities make for a good stage fighting weapon for the films and TV series he works on, not for what makes for a good functional weapon for the actual systems of martial arts the historical originals were developed for.

The criticism here that pertains to David Baker can also be applied to the other judges and producers of the show who are associated with the American Bladesmith Society. This is not an organization that is particularly focused on reproducing historically accurate knives and swords. Rather it is a non-profit group of bladesmiths seeking to promote their business interests, and who frequently use historically inaccurate techniques to produce blades that, to the amateur, look historically accurate but frequently are inaccurate in terms of their handling properties (such as the point of balance of the swords), steel quality used, and so on. The primary goal of a smith who belongs to the ABS is to sell cool looking swords and knives to sword enthusiast collectors, most of whom do not practice historical European martial arts and cannot spot the problems. While ABS does promote forging of blades over stock removal of material from sheets of metal, almost no one in ABS uses historically accurate methods of forging, instead using modern equipment and methods to do the forging work. They are particularly focused on promotion of pattern welding forging, often mistakenly referred to as ‘Damascus’ today due to ABS founder Bill Moran believing that pattern welding forging produced the same results as historical Damascus steel.

While the American Bladesmith Society has certainly had a positive influence in the promotion and revival of forging knife and sword blades, the reality is that the techniques are ahistorical and they often promote historical inaccurate ideas about swordsmithing and swordsmanship as a result of these irregularities.

This ahistorical aspect of the forging process used by ABS smiths plays into the kinds of destruction tests that are done to the weapons on the show; tests that historically accurate swords might not actually be able to pass. This matters for the Forged in Fire show as the tests on the show are based on criteria created by the ABS for their Journeyman and Master Smith levels. This means the contestants, knowing the types of destruction tests their pieces will be performed with, forge their weapons to pass historically inaccurate destruction tests and therefore end up producing swords that are historically inaccurate in many ways, primarily in terms of blade geometry designed to endure the destruction testing. This is further compounded by how Doug Marcaida does not know how to use the swords tested on the show, and swings them as if they were a baseball bat.

The problem with making the judges of the show people who specialize in movie props and decorative art pieces instead of people who are experts in historically accurate weapons is that the mistakes common to the prop weapon and art knife industries become the basis for the show’s rules and criteria for judging. One of the biggest problems with modern swordsmithing is that most smiths do not make swords that are historically accurate in regards to hilt design, blade balance, flexibility and often even blade type for the period. What they primarily do is make swords that are imitations of mass produced designs commonly made in China and Taiwan, which themselves are usually based on photos of historical works and produced as cheaply and quickly as possible. So they make replicas of replicas that themselves are not historically accurate.

While the American bladesmiths frequently do use better forging techniques and materials than what can be ordered from these cheaper forges in Asia, the reality is the smiths are not producing swords designed to imitate surviving historical pieces and whose handling characteristics often make them poor functional weapons. The smiths are primarily making copies of other weapons that were ahistorical copies, which have problems in their points of balance, blade thickness, hilt construction, etc. None of this is obvious to the smiths because they have little to no experience with actual historical weapons or any specialized knowledge about their usage.

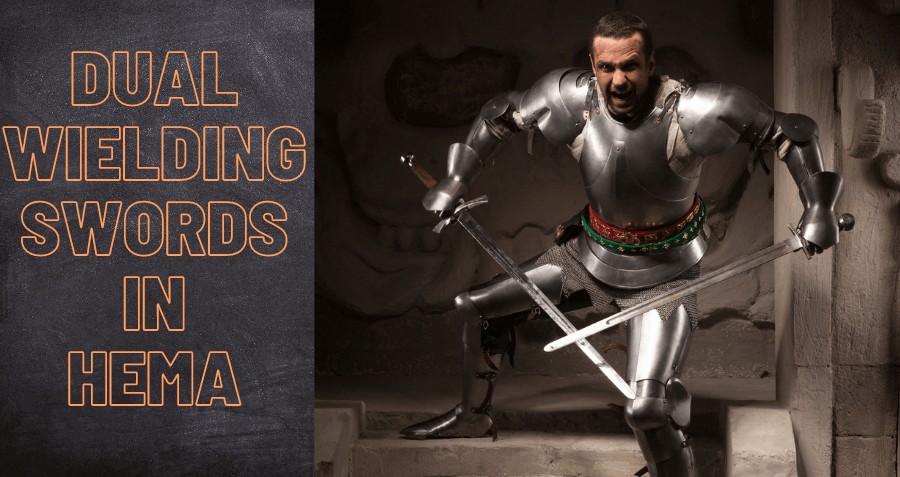

Criticism #3: The Forged in Fire Producers Ignore All Research and Findings of the Historical European Martial Arts Community

One major point of criticism is that no one on the show Forged in Fire has any familiarity with the Historical European martial arts community, which does have people who are both knowledgeable about how to correctly use these weapons and smiths who understand the differences between popular replicas and surviving historical weapons from this time period.

One of the things the global HEMA community has benefited from over the past few years is improved quality of training weapon simulators that aim to more closely match the handling characteristics of surviving swords. These training weapons are produced by smiths who understand what qualities a sword actually needs to possess in order to survive the rigors of blade against blade combat; otherwise they break or handle poorly in the bind. Yet, almost no one in the American Bladesmith Society community produces training weapons for the HEMA community, and those that do are not participants in this show. Consequently this technical knowledge about what makes for a good functional and historically accurate sword does not make it onto the show Forged in Fire, the same way that the show Knight Fight also rarely depicted any historically accurate medieval knight fighting techniques. Instead, ABS style destruction tests are done. A sword can pass these tests yet still have poor handling as a functional weapon. In fact some of these ABS style destruction tests don’t actually make any sense for certain types of sword blades.

As an example of this, let’s look at a clip from an episode in season seven where the contestants were asked to forge ‘Musketeer rapiers’.

This 10 minute clip depicts several inaccuracies, broken down as follows:

Firstly, despite what is shown in the novel and movies pertaining to this time period (such as The Three Musketeers and The Man in the Iron Mask), historical Musketeer soldiers would not have used a rapier as a side-arm. We know this because, as detailed in the book Les armes blanches : sabres et épées, by Dominique Venner, the Musketeers as a mounted light cavalry unit would have used a backsword, a kind of sabre. This particular style is called a Walloon sword or Mortuary sword today. We know this is the preferred sword for these units because the Marquis de Louvois François-Michel le Tellier (who served as the French Secretary of State for War for the French King Louis XIV) wrote a letter in 1679 that says the King ordered these types of swords from Solingen for his cavalry (musketeers). This makes sense because the best swords for cavalry are ones that can be wielded and swung easily with one hand from horseback, which a rapier as a primarily defensive thrusting weapon is not. While rapiers can certainly be used to deliver cuts, the preferred method of cutting with a rapier is a pull-cut, not the types of above the shoulder cuts delivered with a saber that work well on horseback. Beyond this, the fighting style for rapiers is duel oriented, and not intended for use by mounted cavalry.

You can learn more about historical mounted sword combat in our Path of the Cavalier page,

Secondly, a historically accurate rapier for this time period would not have a blade in the style that is shown in this episode. This style of blade shown in the episode is more properly classified as a ‘side sword’, or a spada da lato in the original Italian. While this type of sword is the predecessor of the rapier and so has some qualities in common with it (and the side sword was still in use during the same time period as the rapier was popular) as mentioned in the previously paragraph it was still not the kind of sword a French cavalry musketeer would have used.

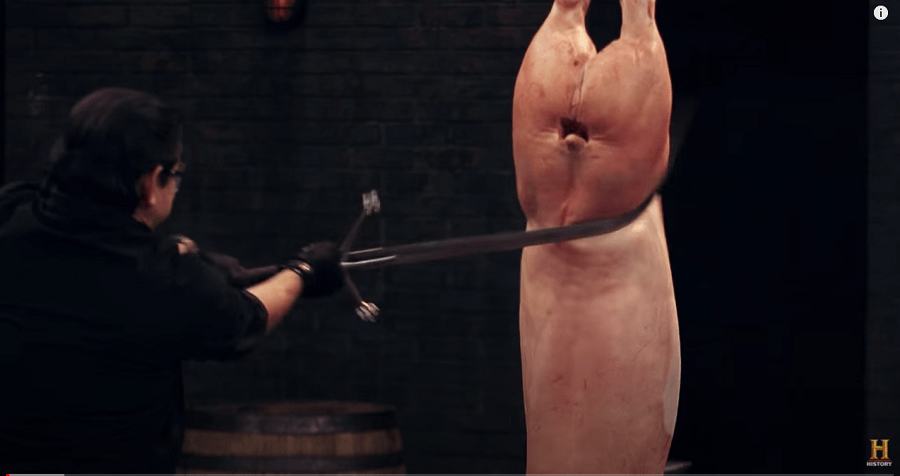

Thirdly, a historically accurate rapier blade for this time period would likely snap in the stress test that David Baker performs against the weapons. This is because historically accurate rapiers have extremely stiff blades that are not designed to bend whatsoever. This is in contrast to an arming sword or side-sword blade, where flexibility is valuable for the type of cutting strikes they perform. So the type of stress test they are performing against these “rapiers” are not suited for the purposes of testing the forging of an actual historically accurate rapier.

An actual rapier has a rigid blade with diamond sectional and acute taper that is as dense as possible to maximize the penetration power of a thrust. This means a genuine historical rapier blade would likely snap if you tried to bend it in a vice the way they do on the show, because flexibility is not desired in such a weapon; flexibility is desired more in weapons that are predominantly used to cut, such as longswords. Even if it doesn’t snap, it’s not going to return to its original shape after you have bent it to this extreme. Besides this, the idea a sword blade would “bend and return to its original shape” is a quality useful for some swords, but not all. This, again, is why ABS style destruction testing isn’t necessarily historically accurate; many historical swords did bend and would need to be straightened, and some swords were not supposed to bend at all.

ABS style destruction tests, such as the bending tests used on the Forged in Fire show, are meant for spring steel alloys and blades of certain geometry. They have become popular among ABS smiths because the bending tests make for good marketing of the blades. Yet as mentioned, historical swords did not always do this. The flexibility of blades used for swords throughout history ranged by their intended function, and so flexibility primarily depends on the blade geometry. This is why swords meant for thrusting, such as rapiers, are less flexible than longswords. Still, most swords used for warfare did not possess the qualities of modern day spring steel alloys such as those preferred for use by the Forged in Fire show contestants as a response to the ABS testing criteria, where bending the blades to extreme angles and the blade returning to its original desired straightness is something desired for grading. This ability for a blade to easily return to shape after an extreme bend is an ahistorical quality for the majority of swords, and in some types of swords such as rapiers, actually makes it less effective for its intended usage. Simply put, a good rapier should fail this bending test, not pass it.

You can learn more facts about how rapiers were actually used in our article, ‘What is a Rapier? Clearing up Common Misconceptions’.

Almost every episode of Forged in Fire has these kinds of historical errors in them that misinform the audience about the sword types featured in the episodes. While this article does not focus on every mistake that has been made in each episode, you should be able to understand from these spotlighted examples why the television series does a poor job of educating the public about historical swords and swordsmanship. It frequently gets the historical facts wrong, it promotes ahistorical forging techniques and sword characteristics, and the show producers neither know how to use the weapons that appear on the show, nor do they fully understand their history.

Despite the high production value in how the show is filmed and edited, the content of the show is actually very amateurish in its advice and information about swords. Consequently, Forged in Fire has little value as a history edutainment program.

The Forged in Fire show producers could correct these mistakes for future episodes by taking the time to read better sources of historical European swordsmanship and the companion books many in the HEMA community have written about these subjects. There are links to these books on our website on the following pages.

The only redeeming quality about the show Forged in Fire is that it is helping grow interest in sword forging and swordsmanship. Hopefully fans of the show will discover HEMA and learn more about authentic historical swordsmanship and martial arts as a result.

****

If you’d like to learn more information about historical European martial arts swordsmanship please check out our Learn HEMA page for a guide to learning about the historical weapon that interests you. You can also find more guides we’ve written about other topics at our Helpful Guides page. You can also join the conversation at our forums or our Facebook Group community.

5 Responses

Awww, some poor “expert” wants to complain about another expert, so they feel better about themselves.

I could write an article about how so much of YOUR bullshit is wrong, but wait…that would mean you worth the effort. And you’re not.

Thanks for pointing out some of the failings of this show. It’s definitely for entertainment purposes only. I’ve been a HEMA student since 2011, and was promoted to instructor in 2017 in the Fiore and Iberian traditions.

It’s a shame that so little research is put into the show that is supposedly historic. I tried to watch a couple episodes from season two on Netflix.

6 of the final challenges are swords from fiction. The first episode was the sword of Perseus and one of the challenges was wailing on a chunk of rock. The sword breaks and the blade hits the judge (Dave Baker?) in the hand. His glove saves him, but who in the world let’s them do destruction testing in short sleeves and no face or neck protection (other than safety glasses)? It’s stupidly neglectful and not only is it a bad example to set, it’s downright dangerous.

Thanks for the article, really appreciate it.

Such a wonderfully detailed and well-written article! I had seen a few episodes, and many things felt really odd to me, but I couldn’t put a finger on it. The vibes were off- it feels like the judges and Marcaida are more interested in a contest of presentational manliness than actual knowledge and respect for the history and art of swords. Thank you for all your work in critically analyzing this show!!

In response to Sam’s reply of November 26, 2021. Sam, you are an ignorant “infotainment” douchebag- now run along and play nice with the other douchebags…

Great article that presents the facts, and was still too soft on these clowns in my opinion. There is a lot more to criticize here. I have always noticed that these “experts” in many of the episodes, decide to beat the hell out of the blade edges, and THEN do a sharpness test- LOL! This in no way reflects the smiths ability to put a good edge on a blade, and if it is meant to show blade durability it fails there too because nearly any good sword blade will become deflected and maybe even chipped if it is used improperly like these dummies do, Yes, perfectly good blades would take damages in battle, but can and were re-sharpened and continued to be used for possibly decades. Also, the show’s “experts” are ALWAYS complaining about swords having grips that are too large or too small, or that the blade seems too heavy or overly light. They do not realize that any type and style of blades were many times forged for a particular user, and therefor had these usually slight differences in them historically. Lastly, Doug Marciado, in addition to his obviously inadequate training, is smaller in stature, and is definitely nowhere near as physically powerful as most of the European soldiers, men-at-arms, warriors, and knights that wielded the western style blades historically- so using him as a tester of what could be done with these weapons is pathetic and laughable. As a matter of fact, the guys over at Cold Steel produce much better cutting test videos that this show produces- period.